The Germanic languages like to pile up nouns. The Romance languages virtually forbid it. The English lexicon, betwixt and

between, has traditionally accepted nouns in pairs with no hesitation. Examples are book store, love affair, deer crossing,

and state university. Three nouns in a row used to be the outer limit and is a rare find in English prose before 1950. Now

we daily encounter excrescences like “growth trend pattern” and “consumer price inflation” and even,

hold your hat, “U.S. Air Force aircraft fuel systems equipment mechanics course” (from a Long Island newspaper).

Nounspeak is not grammatically wrong. We’re concerned here with good style and with clarity and with avoiding problems

for ourselves. Space ship is not a problem. Space ship booster rocket is the beginning of a problem. Most writers would,

I trust, try to find alternate phrasing. But more and more we’re having to accept decided problems such as space ship

booster rocket ignition system. I suggest it’s time to back up.

Scientists love Nounspeak. Anyone hearing them joust

with their mother tongue must lament the change of standards since the Royal Society took as a motto, Nulla in Verba, more

than 300 years ago. Bureaucrats also love Nounspeak. Certainly the military loves Nounspeak. Would you ever guess that target

neutralization requirement means ‘the desired dead’? Or that airplane delivery systems might mean “bombs”?

Here’s the National Academy of Science discussing military research: “Work has included development of empirical

and rational formulae for aerosol survival, formulae for predicting human lethal dose, and quantification of disease severity.”

(They’re talking about germs and poisonous gases.) And most of all the “soft sciences,” such as psychology,

education, sociology and anthropology, love Nounspeak. A prize of some sardonic sort ought to be presented to the behaviorist

quoted in Science Digest who concocted place for goods purchase. It takes a minute to realize he’s thinking about ‘stores.’

The pattern is that people with little to say turn to Nounspeak for pompous packaging, while those with something unsavory

to say find friendly camouflage in Nounspeak’s abstractions and opacities. Who can forget body count?

At a glance Nounspeak might seem a natural development, like the disappearance of the distinction between who and whom or

the evolution of a slang word into polite speech, but it is only natural in the sense that foods such as breakfast cereals

are a “natural” development in modern society. Normally, a language is shaped by the intellectual writers at

the top and the great mass of not-so-intellectual speakers at the bottom. But Nounspeak, like breakfast cereals, is largely

an artificial imposition, perpetrated by that growing multitude in the middle with from one to four years of college. Not

at all restrained by any sense of educational deficiency, this multitude talks to dazzle its own ears.

People

aren’t broke any more. They have a money problem or a bad money situation. Discontented consumers (real people) have

become consumer discontent (an abstraction, like so much Nounspeak). Weathermen don’t predict rain any more: now it’s

precipitation activity.

There may be a metaphysical dimension here. People often have the sensation that they

aren’t being heard. So they keep lumping noun on noun, as though by saying the same thing two or three times, they’ll

be understood across the existential void. Can you think of another reason for Newsweek’s startling duo, inlet cove?

(One can hardly find two more perfectly synonymous words in English? So why use both?) And rain postponement dates recently

appeared on a sign in the subway in New York.

Nouns must comfort with their

solidity. They seem to pin matters down, to freeze life, to ward off future shock. But it’s largely a sham. Life is

flux and process. Verbs are truer to this constant change; and expert stylists have always recommended reliance on verbs.

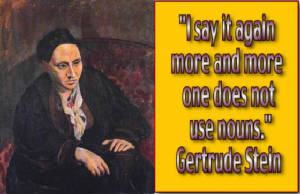

Listen to Gertrude Stein railing against nouns in “Lectures in America”: “Things once they are named the

name does not go on doing anything to them and so why write in nouns. . . .And therefore and I say it again more and more

one does not use nouns. . . .Nouns as I say even by definitions are completely not interesting.” And Gertrude Stein

was speaking about nouns in meager doses, not the excesses here labeled Nounspeak.

Poor Gertrude Stein. Alive today,

she could not read the front page of any newspaper in the country without finding a surfeit of nouns, many of which can be

cut entirely with no loss of sense. The favorite freeloaders are area, situation and problem. One of Nounspeak’s major

linguistic discoveries is that you can attach any one, or even two of these words to any other English word with no change

of meaning. The gain in precision is illusory but the loss of clarity is real.

Nounspeak shares common ground with

jargon and bombast and gobbledygook and prolixity and confusion of whatever sort. But Nounspeak does seem to be the most sharply

defined of these phenomena and may be the more interesting in exhibiting its own rudimentary “grammar,”the devices

by which perfectly fine English is “translated” into Nounspeak.

The first and most obvious of these

devices is: never use one noun when two (or three) can be rummaged up. Contemplate these words: subject; interim; spending;

transition; passengers; and contract. Is not each a sturdy soldier of a word, wholly equipped by itself and ready for any

mission? But these excellent nouns split in Nounspeak to become: subject matter; interim period; spending total; transition

period; passenger volume; and contract agreement. (All examples are from the press.) Note that nothing is added except the

extra syllables. Like germs, one noun splits into two, and then one of those can become two again.

A second technique

for subverting English into Nounspeak requires changing strong, aggressive verbs into weak nouns. We control pests is English.

We accomplish pest control is Nounspeak. It’s hard to see any good reasons for this device. But many variations can

be found in the press. The idea is to smash those verbs. Mothers don’t feed infants, they practice infant feeding; teachers

don’t educate any more, they work at student education; politicians don’t appeal to voters, they have voter appeal;

readers don’t respond, they show reader response.

A third technique diminishes clarity by disdaining the

possessive ’s or of. “Nixon had this to say about the Agnew criticism. . . .” Heard on radio, there is no

way of knowing whether Agnew was criticized or criticizing, except by context. Paradigmatically, “B’s A”

and “A of B” are being changed wholesale into “BA.” Thus rate of change, which is smooth and flows

easily into the brain, becomes change rate.

In the years ahead English will depend much more heavily on nouns than

Gertrude Stein might like. But it’s reasonable to ask that our writers and editors steer us away from Nounspeak’s

worst excesses. We’ll know the tide has turned when the IRS whittles its Tax Schedule Rate Chart down to Tax Rate Chart,

then to the very sensible Tax Chart, then—unlikely victory—to Taxes, which is what they were trying to say all

along.

Article 5>>>"Noun Overuse Phenomenon Article" first

appeared in Verbatim, Feb., 1976. It was included in "Subject and Structure, an anthology for writers" (1981), a

college textbook. The article was also chosen for Verbatim's own big best-of anthology, 2001. (Verbatim, the Language Quarterly,

can be found at VERBATIMMAG.COM)

In fact, Nounspeak is less a nuisance now than when Articles 4 and 5 were first published, so maybe

they did some good.